We sat down with Valerio Tiberi to talk about creativity and technique in stage lighting.

Theatre (…) is the only place where you can rediscover darkness.

Valerio Tiberi is one of the most sought-after lighting designers in the European theatre scene. His professional range spans from opera productions in emblematic venues like the Opéra Bastille in Paris and Teatro alla Scala in Milan, to international musicals such as The Phantom of the Opera, Cabaret, or West Side Story; ballet (A Thousand Tales, Alice in Wonderland, etc.), and haute couture fashion shows for brands like Valentino and Dolce & Gabbana. He has received numerous awards, including the Italian Musical Oscar and Best Lighting Design.

His work strikes a natural balance between technical precision and aesthetic sensitivity —which is no small feat. In this interview, he opens up about his creative process, his reflections, and the challenges of lighting vastly different worlds: the theatre stage and the fashion runway.

The challenge of lighting a classic

Tiberi recalls that his relationship with LETSGO dates back at least to 2016, when they produced Dirty Dancing in Spain for the first time:

I came with Federico Bellone; we were the original creative team. Since then, we’ve done many productions [with LETSGO], but without a doubt, the most successful one is The Phantom of the Opera.

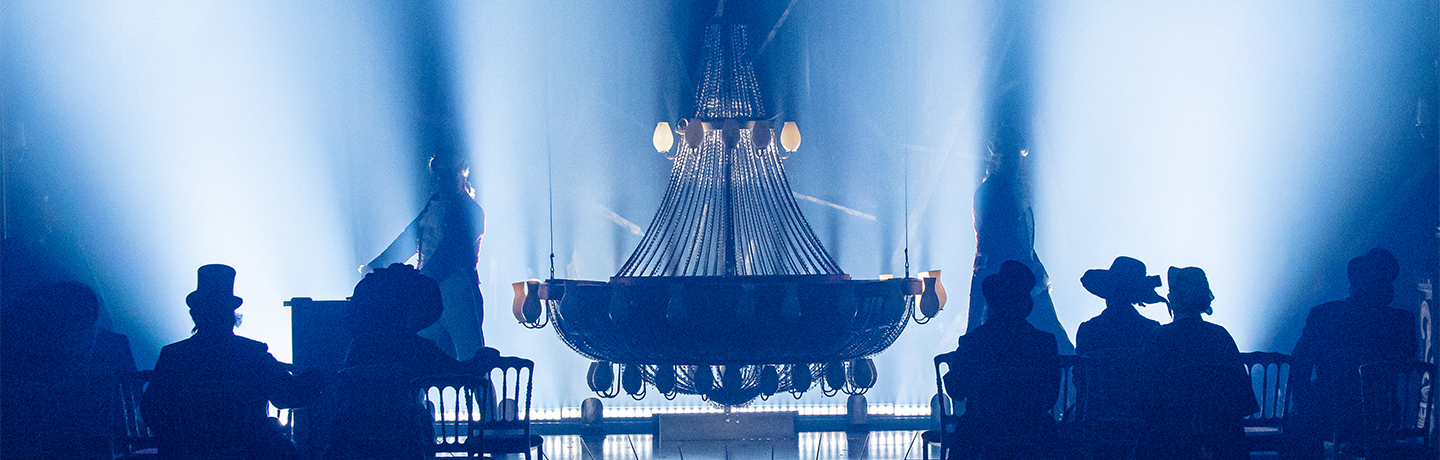

Being part of the first Spanish-language production of one of the most successful musicals in history was a challenge in every sense. Tiberi remembers staging Phantom at Teatro Albéniz as “a very difficult project.” This is where the intricacies of lighting design come into play, when theory meets the hard ground of practice:

The biggest challenge was finding the physical space to place the light. We can all come up with incredible ideas, but my job is to make them into reality.

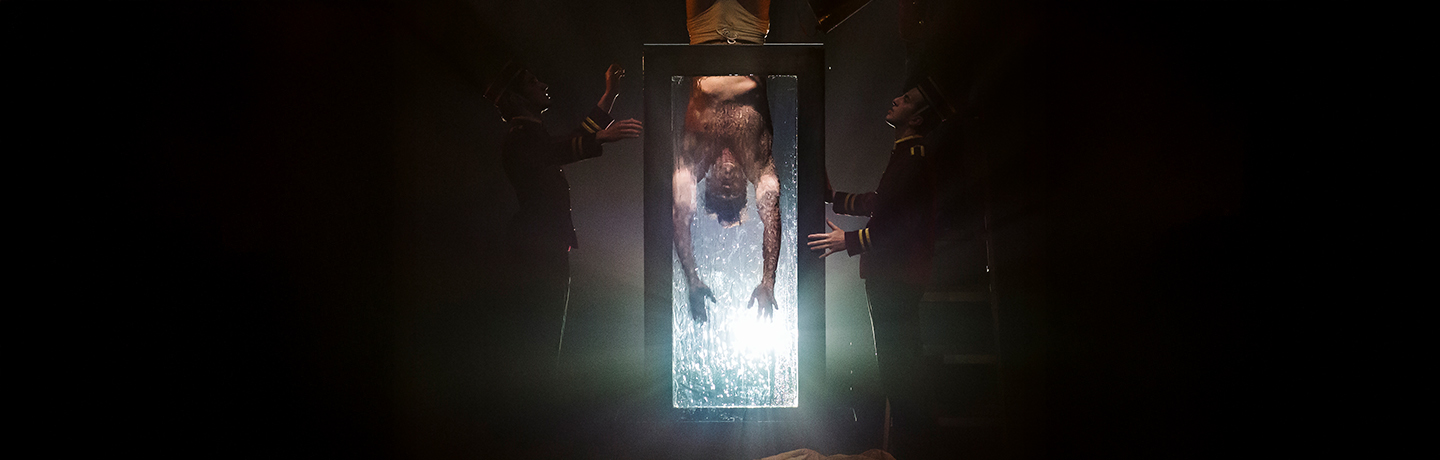

Lighting design by Valerio Tiberi for The Phantom of the Opera (Madrid production). Photo: LETSGO.

It was one of those times when art has to come down to earth: adapting to budgets, technical layouts, timelines, and spatial limitations. Finding the perfect spot for the light, and projecting from there.

We used very powerful light sources that could do several things at once: specials, washes, effects. We worked a lot with light tilting to create depth, and we also used smoke, fire… fire is light, too, of course.

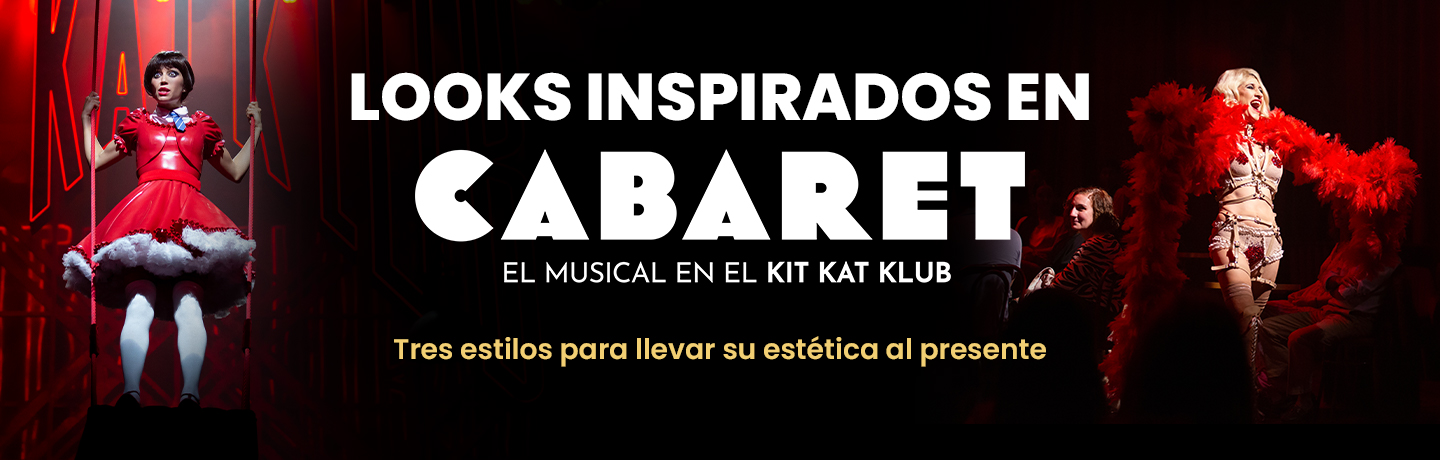

An artist’s greatness often lies in their versatility. Cabaret is a whole different beast —but naturally, Tiberi embraces the challenge:

In Cabaret, the approach is completely different. It’s an immersive production and although we’re still in the creative process, the challenge is once again the same: finding space for the lights. Only this time, the light is exposed. In Phantom, it was hidden. The audience didn’t see it. In Cabaret, the lighting is part of the set. Everyone will see it.

Thinking like the audience

Lighting design is not just a technical craft. How do you think about a show when you’re a creative but can’t lose sight of the surgical precision that light demands? Luckily, artistic environments are fertile ground for questioning and transformation.

Tiberi is clear: the key is thinking like the audience. In the end, it all comes back to emotion and to human reaction:

There’s no one rule. I adapt to each situation. For example, with Cabaret, I started from the tools: I knew I needed dynamic, effect-driven lighting. In Phantom, it was the opposite: storytelling was my starting point.

But in both cases, I try to keep an artistic mindset from the beginning. I like to think like the audience. The audience doesn’t know if it was hard or easy to achieve an effect; they only know if it moved them. That’s why I try to understand how the human mind reacts to light, to color, to stimuli. And that changes depending on the type of show, the city, the society. It’s not just design: it’s psychology.

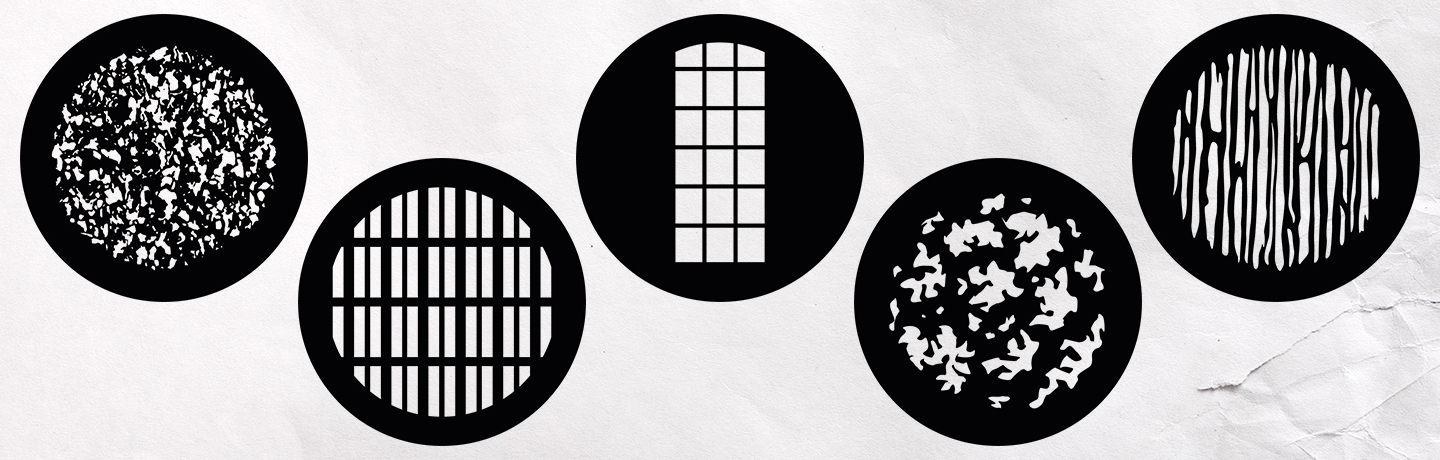

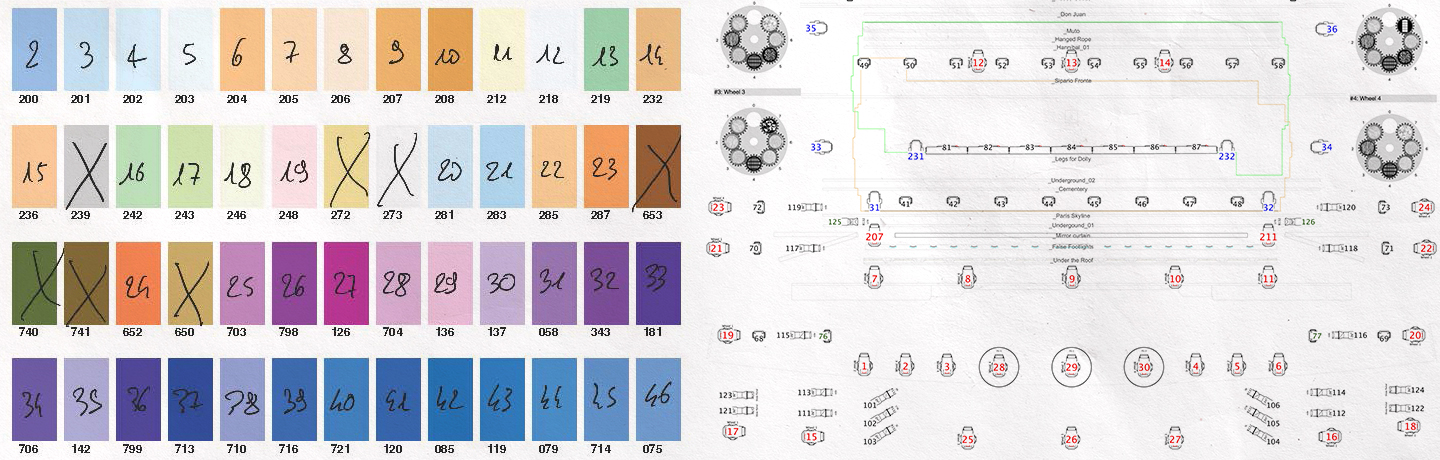

Custom Gobos used on The Phantom of the Opera. Courtesy of Valerio Tiberi.

Rediscovering darkness

Tiberi is fascinated by a deeply contemporary concern: in a world blinded by light (computers, phones…) we’ve become unavailable to darkness. We live in a state of overexposure, often without even realizing it.

Theatre, like some exhibitions, is the only place where you can rediscover darkness. That’s why I always start from the dark. And from there, I build layers. I begin with the black, then work on the amount of light: the white. And if needed, the colors come after. Contrast is essential. I’m not just talking about aesthetics; I’m talking about creating an intimate experience, something the audience doesn’t find in their daily lives.

“Rediscovering darkness (…) an intimate experience.” To train the mind to appreciate privacy and reflective environments —so often linked to solitude and twilight— has become a monumental act. In this sense, framing theatre as a space that revives our most primal thoughts and relationships isn’t nostalgia: it’s a new form of approach, born from our modern context.

Can AI understand theatre?

Another hallmark of our times: new technologies and the relationships we forge with them. Tiberi acknowledges that AI has helped him streamline tasks and compare ideas:

It’s like a secretary: I feed it images, concepts, and ask it to try out atmospheres. But of course, AI doesn’t know where to physically place a light in the theatre, or which type to use, or when. It helps optimize, expand your thinking, but not solve the essentials.

I mostly use it for dramaturgy. I create mental maps of the show, there, it’s useful. But you need time. If you’re working, you’re working. Still, I think many professions could benefit from AI if used wisely.

Despite growing discussions about whether human creativity can be replaced by algorithms, Tiberi reminds us that some things can’t be substituted. Asked about a moment where lighting was crucial to solving a dramaturgical challenge, he shares:

In Houdini, in Italy, one of the last scenes was very hard to resolve. We talked for weeks about how to stage it… and in the end, I did something very simple in the theatre and it worked. Sometimes we overthink things, and the solution is in the simplest move.

Lighting design by Valerio Tiberi for Houdini (Italy production).

Being a designer today: the power of active experience

In a world where instinct and hands-on experience make all the difference, Tiberi knows exactly what he’d tell a young lighting designer starting out:

Nowadays, with all the tech out there, it’s easy to reach an average level. But getting to the top is harder than ever. The key is real experience. You need to be in the theatre, live the space, rehearse, test. Be there at least 300 days a year. And travel. See shows, museums, exhibitions. Not just modern ones, classics too. Go to the Louvre, to MoMA… Start from what’s tangible. Don’t stay in one country, or one style.

On his experience teaching at the Accademia Teatro alla Scala, he adds:

I don’t want to be a traditional professor. I want to speak from experience, what’s worked and what hasn’t. I try to involve my students directly in the theatre. That’s where real learning happens.

Color List used for the lighting design (left) and Designer’s magic sheet (right), both used on The Phantom of the Opera. Courtesy of Valerio Tiberi.

Fashion vs. Theatre: two worlds, two timeframes

As mentioned earlier, Tiberi’s work isn’t limited to the stage or the classroom. He’s also designed lighting for fashion shows, where atmosphere and storytelling —when present— play a secondary role. But where does the real difference lie between stage and runway?

It’s all about timing. In fashion, preproduction is long, but setup takes just two or three days. And the show lasts, at most, twenty minutes. In that time, you run seven or eight cues: the intro, models entering, the runway, the finale, the exit.

It may not sound like much, but it’s a massive job, with last-minute changes, contradictory decisions… sometimes the day before.

Above all, it’s about the clothes. You need to light the garments with natural-looking light, without altering colors, minimizing shadows. The image must be clean, sharp. Sure, you work on the mood, but ultimately, it’s about showcasing the clothes. It’s about showing and selling.

And the goal is completely different from theatre. In a fashion show, what matters most is what ends up on Instagram. Lighting has to be tailored for smartphones, not for the human eye. And there’s the live stream too, all the major brands do it now.

The emotional impact of light

A profession that walks the line between creativity and technicality but that, above all, demands a sensibility centered on the audience. In this sense, theatre stands as a master at evoking the deepest emotions.

Lighting design by Valerio Tiberi for Natura Encesa (Barcelona production). Photo: LETSGO.

In musical theatre, the show comes together during previews, where you polish the details. The most emotional moment is the premiere, that’s when you can finally sit back and enjoy. Opening night is when you let go and just watch.

The premiere is the first glimpse into the emotional impact a piece can have, not just on the audience, but on the team behind it. In September 2024, Valerio Tiberi returned to Madrid after nearly a year, not because of Phantom, but for unrelated reasons. Still, he went back to the Albéniz to see the show again:

I was crying the whole time. After a year… it made me cry. When that happens, it’s a good thing.

By The LETSGO Pen, Claudia Pérez Carbonell, on July 15th, 2025

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]